Onsite Maori carving studio

The Treaty of Waitangi is New Zealand’s founding document. It takes its name from the place in the Bay of Islands where it was first signed, on 6 February 1840. This day is now a public holiday in New Zealand. The Treaty is an agreement, in Māori and English, that was made between the British Crown and about 540 Māori rangatira (chiefs).

The very best part of our day was a deeply immersive walking tour, led by a proud Maori woman with a wicked sense of humor. Here's one of the waka taua (war canoes) stored in a waka house on the grounds.

The waka are still used every year on Waitangi

Day, moved into the water via rail, though originally

logs were used to roll the vessels to water.

The waka are made from kauri trees, ths longest below from three trees.

The beautifully carved stern post helps the waka keep its balance.

A section of the waka house.

Lieutenant-Governor William Hobson had the task of securing British sovereignty over New Zealand. He relied on the advice and support of, among others, James Busby, the British Resident in New Zealand. The Treaty was prepared in just a few days. Missionary Henry Williams and his son Edward translated the English draft into Māori overnight on 4 February. About 500 Māori debated the document for a day and a night before it was signed on 6 February.

Busby's house

Our guide emphasized the debt owed Busby by both Maori and Pakeha (Europeans, New Zealanders of European descent).

Our guide

The Treaty is a broad statement of principles on which the British and Māori made a political compact to found a nation state and build a government in New Zealand. The document has three articles. In the English version, Māori cede the sovereignty of New Zealand to Britain; Māori give the Crown an exclusive right to buy lands they wish to sell, and, in return, are guaranteed full rights of ownership of their lands, forests, fisheries and other possessions; and Māori are given the rights and privileges of British subjects.

(H2 note: the nub of the issue, near as I can tell, was and remains this first article.)

Then it was time for a Maori cultural experience, held inside the elaborately carved marae, or meeting house. It was full of music, some fierce haka-like movements with long sticks, and some celebratory movement and song.

The walls of the interior, papered with woven flax and more carvings

Different understandings of the Treaty have long been the subject of debate. From the 1970s especially, many Māori have called for the terms of the Treaty to be honoured. Some have protested – by marching on Parliament and by occupying land. There have been studies of the Treaty and a growing awareness of its meaning in modern New Zealand. (If you want more still it's here)

The Queen of Flat Whites was overstimulated, but not so much that she didn't head straight for the cafe.

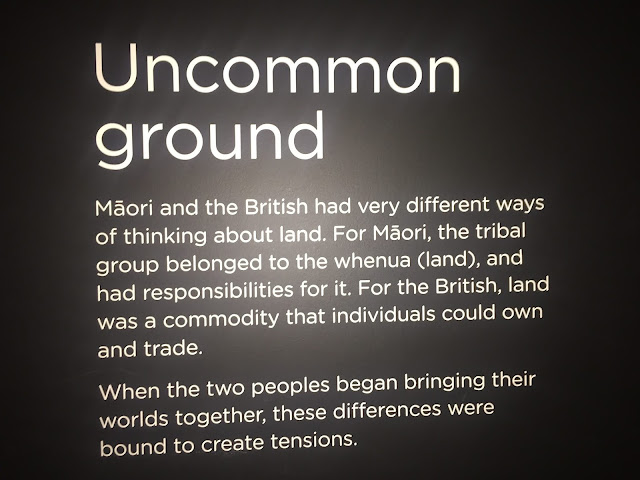

Then we toured the museum, where history became just that much more intriguing. Here's one couplet of photos that seems to confirm that human relationships are central to everything. Read the story and then look at the picture.

Tensions indeed. Language is incredibly powerful.

More skilled relationship building

(get in good with the missionaries and you're golden)

The prism of perspectives is never-ending. A stimulating, thought-provoking day.

No comments:

Post a Comment